But if we look just outside British symphonic prog, we still find many masterpieces being released during the ‘latency years’ situated between the supposed death of prog and its rebirth in the Eighties (with neoprogressive). The main factors responsible of such an ‘assisted suicide’ were, together with the Anglo-symphonic stereotype, the critics willing to follow the popularity of punk. But wasn’t it always the case? My paper argues that the ‘Anglo-symphonic stereotype’ that associated prog music with the British world – and especially with the most popular form of progressive rock developed there, namely symphonic progressive rock – played an important role in the promotion of an historiography that firmly puts an end to the history of prog around 1976-1977. Steven Wilson, Anathema, Haken, TesseracT), it seems hard to conceive prog as a British phenomenon. Today, despite many important artists still being British (e.g. Yet prog was indeed a ‘many-headed beast’, and its form has changed a lot through time and space. Progressive rock has always been seen as a mainly British phenomenon: all the major bands from the genre – like King Crimson, Genesis, Yes, ELP and many others – are British (and English in particular). To further nuance our understanding of ‘what prog may be’, I use postmodern lenses to investigate the post-progressive/neo-progressive dualism, and argue that they could be seen as two opposite declinations of an attitude that might be postmodern at its core. In my paper I cross the findings of an empirical survey I posted in strategic locations of the internet with a selection of songs I analysed, aiming to understand which entries of the resulting set of musical features and values – nurtured by the perspectives of scholars, magazines, festivals and listeners – play a defining role for the ‘progressive attitude’. The Flower Kings, Spock’s Beard, Big Big Train, etc.), and taking especially into account those features that prog communities consider to be valuable for the genre they love (Frith 1996, Gracyk 2007)? How can we differentiate the ‘progressive attitude’ mentioned above from a broadly ‘experimental’ approach (Martin 1998), and make sense as to why some ‘limbo-artists’ who share plenty of musical features with progressive music are generally not included in the ‘canon’? Moreover, can theories of musical genre (especially Fabbri 1981, Quintero 1998, Holt 2007, Lena 2012) be of some use when further delving into this constellation of sub-genres? Steven Wilson, Dream Theater, Opeth, Tool, Anathema, etc.) and neo-progressive (e.g. Is there a way to understand and define present-day progressive music, without neglecting the meaningful differentiation between post-progressive (e.g. However, so wide is the spectrum of musical phenomena included in contemporary progressive that the question ‘is this prog?’ – very common among users commenting songs and albums in online prog forums and communities (Atton 2001, Ahlkvist 2011) – remains difficult to answer. Several scholars have agreed that ‘progressive’ may define a particular attitude towards musical creation, rather than an actual musical genre (Sheinbaum 2008, Saluena 2009, Anderton & Atton 2011, Hegarty & Halliwell 2011). It questions the use of the term ‘neo-progressive’ (now typically used to refer to this period of music and a network of styles which supposedly developed from it), and examines why the putative ‘progressive rock revival’ of the early 1980s, as it was referred to in the press, failed to gain traction at that time. This chapter explores this poorly understood and largely ‘underground’ era of progressive rock’s development by examining print and media coverage of the time and the exploring the influence of both punk-rock and the new wave of British heavy metal.

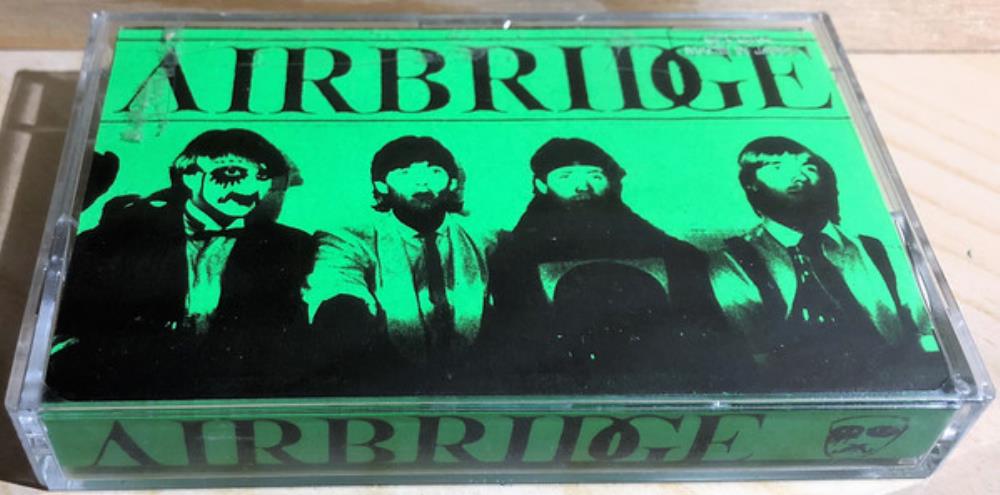

These, and many other bands of the time, managed to foster trans-local networks of progressive rock fandom based principally around live performance, and while recording contracts were obtained by a few bands, many more adopted an independent stance by self-releasing cassette and vinyl demos and albums. The most successful band of the revival was undoubtedly Marillion, yet many other bands emerged during the early 1980s, including Pallas, IQ, Pendragon, Solstice, and Twelfth Night. However, ‘progressive’ rock enjoyed a nascent revival in the early 1980s that had continuities with the 1970s, yet developed in its own particular ways. Progressive rock’s ‘golden age’ is typically defined as a decade beginning in the late 1960s and ending in the late 1970s when progressive rock’s most visible and successful acts had either run out of steam, broken up, or begun to adopt a more mainstream, radio-friendly style.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)